Wednesday saw the release of the UK Budget. Frankly, after a long wait filled with endless speculation, the final result was something that delivered a little to just a few (a consistent feature of this government!). Its delivery had been preceded by several, early insights to its contents. In addition, the OBR (Office for Budget Responsibility) had also been consulted to assess its likely impact…..a clear sign the Chancellor was trying to appease markets, disguise her lack of (self) confidence and avoid any major embarrassments. Then, on budget day, the OBR “mistakenly” released the entire budget on its website before its full details were announced in Parliament. It was entertaining to say the least!

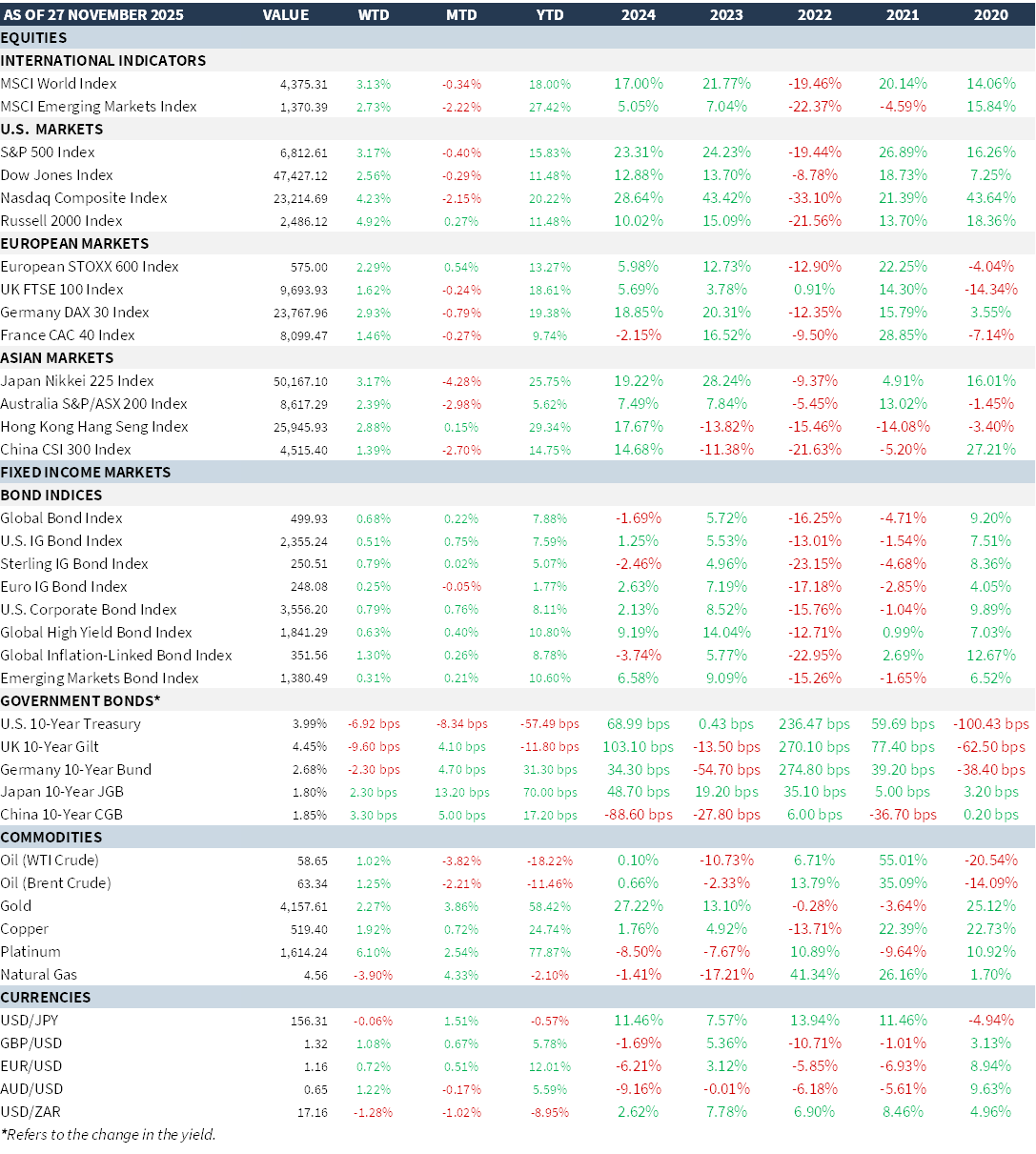

The Chart below summarises the effect of the budget on tax receipts, since March, on forecasts by 2030 (in £bn):

The personal tax threshold freeze (aka Fiscal Creep) is taxation by stealth. Most people aren’t even aware it’s happening and yet it raises revenue without the Chancellor even having to change a single tax rate. This measure is estimated to raise £8.3bn by 2031. It works like this: by keeping the income tax thresholds unchanged, then as wages rise (e.g. due to inflation or productivity gains), more workers end up crossing into the higher tax bracket over time (hence the stealth nature of it). Furthermore, those already in that bracket pay more tax on a larger share of their income. Finally, some may even lose access to benefits or allowances because they end up crossing income limits. This was a U-turn for the current government – they had promised there would be no further freeze once the existing freeze (imposed by the previous government) would come to an end. Another, controversial change was to the Salary Sacrifice scheme – something designed to encourage people to save for their pension. It allows people to take a lower salary and put the difference (i.e. between their original gross income minus the lower, agreed income) into their pension and avoid national Insurance (NI) tax. The benefit to both employers and employees is lower NI tax. Now, the limit (on how much you can put into a pension without incurring NI) is set at £2,000. Any amount above, will incur it. The expected tax raise from this cap is £4.7bn. 10% of government workers and 30% of private workers use this scheme. Other tax measures raise about £11bn and are wide-ranging.

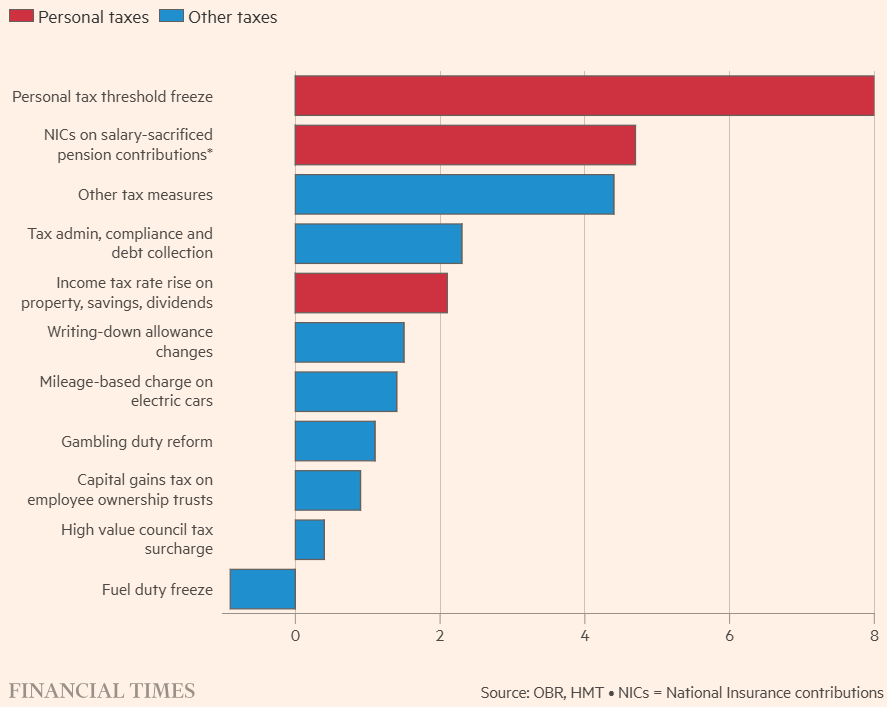

The major problem – and concern – with this budget is that there is a mismatch between the timing of the spending (which is front-loaded) and the raising of the revenue (which is back-loaded). In other words, there is a (slightly) looser fiscal stance near-term (compared to the March Budget statement) but a significantly tighter one further out in later years. This is demonstrated in the chart below. (Note: the “primary deficit” = before accounting for the interest-servicing cost).

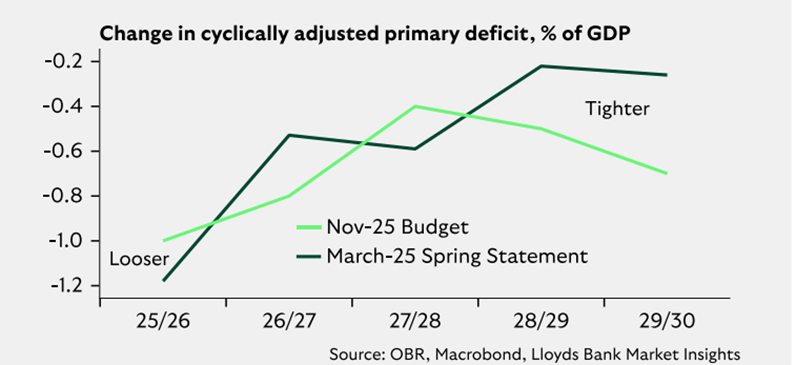

This looser front-loaded stance is why the OBR revised up its GDP forecast to 1.5% for this year (vs 1.00% back in March)….but worryingly have revised down GDP forecasts for the next two years (2026 and 2027):

So why then has this government delivered a low-growth, mismatched revenue/spending budget with the highest projected tax burden ever recorded (since the 1950s)? Because it has tried to balance short end delivery (to honour social pledges e.g. child benefit as well attempting to keep inflation in check with a freeze on fuel duties) with some sort of fiscal control (however cosmetic) to appease bond markets (thereby avoiding another Liz Truss saga). The assumption of higher, projected growth this year (fiscal spending) eats into the projected growth of later years (fiscal drag). By try to lower fiscal drag, they are attempting to restore the fiscal headroom. Think of the latter as the margin of error/cushion created if you deliver on your economic targets & comply with fiscal rules. That rule currently states that by year five, public debt must be falling as a share of GDP. Following this week’s budget, the headroom (in theory!) has gone up to around £22bn by 2030 – assuming nothing goes wrong (i.e. only if economic forecasts play out as planned). Prior to this, it was £9.9bn! It’s like any form of budgeting – if you fall inside your budgeted costs or exceed your budgeted income, you create more wiggle room. That “wiggle room” is your fiscal headroom.

Where does this leave government debt – or more specifically the new issuance needed to fund economic activity? The table below summarises gross issuance (i.e. the issuance of Gilts and T-Bills) to fund the fiscal drag (that’s existing debt that is maturing plus new borrowing to fund the deficit):

| Fiscal Year | Approx. Gross Issuance (Gilts + T‑bills) |

| 2025–26 | £303.7 bn (confirmed) |

| 2026–27 | £270–290 bn |

| 2027–28 | £240–270 bn |

| 2028–29 | £210–240 bn |

| 2029–30 | £180–220 bn |

The decline, over time, reflects the government’s stated objective of gradually reducing its borrowing requirement as fiscal consolidation proceeds. Currently, the government borrows some £120bn to £130bn per annum (to finance the excess spending over receipts aka “living beyond your means”). A key assumption is that this falls to around £50bn by 2029/30 – which is consistent with the post-budget forecasts. Another assumption is that the DMO (Debt Management Office who conducts bond sales and redemptions) maintains a diversified maturity profile. This is an unknown – they mat well shift their preference to more short- and medium- term issuance as signalled in 2025/26. This being so, the yield curve will change as funding yields change at different points along the curve. Markets always obsess about the shape of the yield curve and tend to overlook the funding nature that drives yields. If you choose to fund via more short-term issuance, naturally the front end of the curve rises vs the back end resulting in an inverted curve. Textbooks will tell you this implies recession. While it is true all recessions have been preceded by an inverted YC, the opposite is not true!

So is this budget really as “growth-friendly” as it appears while meeting self-imposed fiscal rules? Here’s the good and the bad:

- Certainly, the OBR is forecasting £22bn in fiscal headroom by 2029/30 (a rise of £10bn) but only on paper.

- NI has been cut 2% from Jan. 2026 to help working-age taxpayers and support labour incentives.

- DMO issuance has come in at the low end of expectations for 2025/26 which helps ease bond market anxiety.

- By backloading cuts, the risk of an austerity shock has been avoided – for now.

- By pushing the vast majority of the deficit reduction into 2028 to 2030, they have effectively kicked the can right down the road and well into the next election! It raises serious credibility issues!

- They have included supermarkets in a new tax on businesses where the rateable property value is above £500,000. This will inevitably drive-up food inflation. Supermarkets operate on very low profit margins (e.g. Tesco’s is 2.3%). The further rise in the minimum wage doesn’t help this any further.

- The £18bn of departmental savings are rather fictional. They are not notional cuts, they are real cuts in that departmental spending rises/stays below inflation. This is austerity by stealth and will come back and bite (workers going on strike over pay, declining services, etc.). Included in this is the NHS.

- There is no room for error….the £22bn headroom is wafer-thin to act as a sufficient cushion against macro shocks, rising debt-servicing, any growth undershoot….and so on. Bond markets will have the last say (as they did after last year’s budget).

It is a highly political budget aimed at trying to salvage the Chancellor’s own position & reputation (especially after last year’s debacle). The reality is it delivers little immediate stimulus, backloads consolidation and leans heavily on fiscal drag and spending restraint to create the illusion of control. Finally, what of Gilt yields since the budget announcement (26th Nov.) to the present day? For now, they are holding but it’s early days….see table below:

| Date / Event | 10‑year Gilt Yield | 30‑year Gilt Yield | Explanation |

| OBR Leak (Budget Morning) | 4.42% | ≈5.23% | OBR’s headroom (~£22bn) leaked early → markets interpreted as “more fiscally sound than expected” → initial rally in gilts → yields drop. |

| Budget Delivered (Full Details Released) | 4.54% | ≈5.34% | Market realised consolidation was back‑loaded and short‑term borrowing rises → gilt supply fears return → yields rise again. |

| DMO Remit Published (Post‑Speech) | 4.45% | ≈5.25% | DMO confirmed only £4.6bn extra issuance, which was far lower than feared → supply pressure softer → yields fall again. |

| Initial Post‑Budget Close (Budget Day COB) | 4.45–4.46% | ≈5.24–5.26% | Market volatility settles; traders view the remit as benign but remain cautious about back‑loaded fiscal tightening. |

| Most Recent | 4.44% | ≈5.18% | Yields roughly stable. Market now focused on: (1) near‑term gilt supply, (2) BoE rate path, (3) credibility of medium‑term consolidation. Curve remains slightly flatter as long‑end demand improves. |

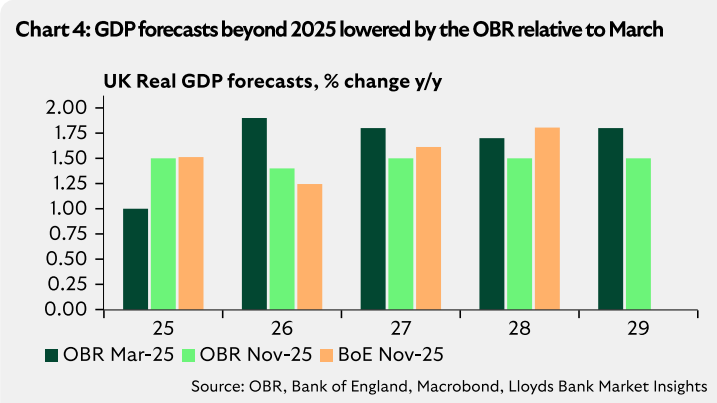

MARKET SUMMARY...

Since last week, the probability of a December US rate cut has increased dramatically and now stands at 83% based on the latest, implied futures pricing (CME). This was driven by some Fed Board members stating their preference for a rate cut in December before standing pat into 2026 and assessing the health of the economy. No surprise that markets have had a good week (see table below) aided by a strong bout of risk-on. US markets are closed due to Thanksgiving. May the festive cheer continue into year-end.